Case File: HIV/AIDS Part 1

- Home

- Long-Term Diseases

- Pandemic!

- Special Exhibitions

- Case File: HIV/AIDS Part 1

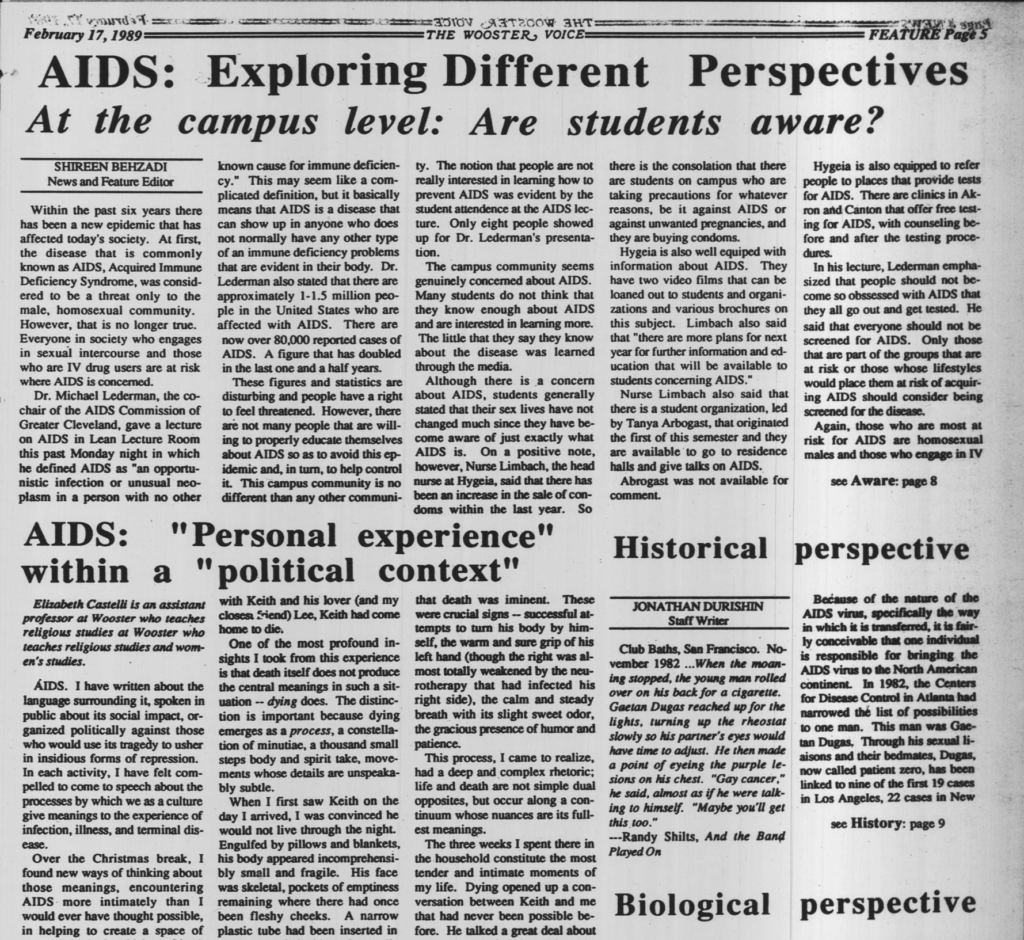

On February 17th, 1989, The Wooster Voice dedicated a feature page to AIDS. At a glance, it seemed that the campus was hosting an active discussion about the deadly virus which several years prior had been identified as HTLV-III/HIV: a retrovirus transmitted through sexual contact, blood, and needles. However, bold letters across the top of the page proved contrary, “ARE STUDENTS AWARE?” The answer was no. When commenting on a lecture given to the campus by the chair of the AIDS Commission of Greater Cleveland, the author noted, “The notion that people are not really interested in learning how to prevent AIDS was evident by the student attendance…only eight people showed up.”[i] The general lack of interest in AIDS among students at Wooster followed a broader trend of a silence surrounding the disease. The virus was considered shameful, and despite contrary scientific evidence, was still associated with gay sex. This can be seen in another article on the same page which, following national discourse, placed the blame for the epidemic on patient zero. The article focused heavily on the patient in question’s gayness and subsequent promiscuity claiming that, “he travelled extensively and picked up men wherever he went.” The article suggested that the man in question continued to have unprotected sex after his doctors told him not to, and concluded that he was responsible for, “countless direct and indirect victims.”[ii]

That is not to say that campus attitudes towards the virus in the late eighties were universal. By covering campus failure to respond to the AIDS crisis, the articles in question, adopted an activist tone. In the same edition of the Voice, Professor Elizabeth Castelli recounted her experience helping her AIDS positive best friend die with dignity. The professor wrote,

“By communicating this personal story, I hope to raise also the political questions concerning the death of my friend. If we as a culture take seriously the heightened consciousness of suffering… [how might that] challenge the silence/death that dominant cultural meanings surrounding AIDS impose?”[iii]

In other words, through her experience, the professor was advocating for an end to the silence and repression the AIDS crisis generated. In totality, despite a general apathy towards AIDS education, the College of Wooster was host to a variety of diverse conversations about AIDS in

[I]Behzadi, Shireen. “At the Campus Level: Are Student’s Aware?” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5.

[ii]Durishin, Jonathan. “Historical Perspective.” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5.

[iii] Castelli, Elizabeth. “AIDS: A ‘Personal’ Experience Within a ‘Political’ Context.” The Wooster Voice. February 17, 1989. 5.

Header: “HIV Infected H9 T-Cell.” The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease. Accessed July 1, 2020. Online at Flickr.