Wooster in World War One

- Home

- Wartime Wooster

- Exhibits

- Wooster in World War One

by Shannon Dade, revised by Spencer Gaitsch

On April 6, 1917 the United States declared war on Imperial Germany, tipping the balance of power in Europe in favor of the Allies. Although isolationist sentiment had dominated Wooster in the early years of the war, a combination of factors, including the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and the interception of the Zimmerman Telegram, had led to its decline and eventual disappearance. By 1917, American sentiment towards Germany had soured and many in Wooster were determined to see the Central Powers defeated.

On the home front, Wooster did all that it could to support the American war effort. Liberty Bond drives were organized, residents volunteered to serve in the United States Army, and farmers worked overtime to produce food for troops overseas. Local newspapers and leaders glorified young men going off to fight and made heroes of the men and women who stayed behind and did without to support them. In this way, World War One brought many people in Wooster together in a way that they had not previously been, yet it also pushed others away. War with Germany had created much anti-German sentiment, which led to discrimination towards members of Wooster’s German population as well as those of German heritage.

Wooster Volunteers in France

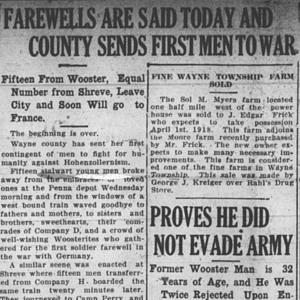

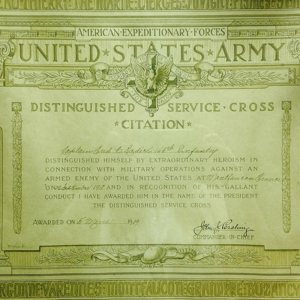

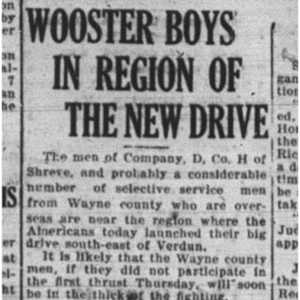

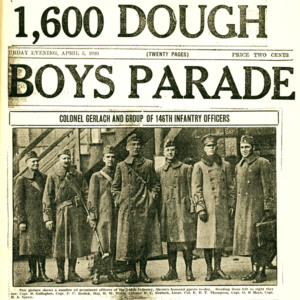

As the first company of soldiers boarded a train and began to depart from Wooster on August 15, 1917, a crowd of townspeople waved them farewell. President Woodrow Wilson had called upon the 8th Regiment of the Ohio National Guard, amongst others, to serve in the American Expeditionary Force that was being deployed to France. Wooster volunteers serving in Company D of the 8th Regiment were led by Major Frank C. Gerlach and Captain Marcus R. Limb. Gerlach. The latter of whom would later be promoted to Colonel and command the entire 145th Ohio Regiment. Less than a year after its initial departure, Company D, led by Captain Fred Redick, participated in one of the most famous operations of World War One: the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

This, and other news from the front, made Company D the pride of Wooster. Wooster residents eagerly awaited the local paper’s weekly reports about “the boys” at the front. The Wooster Daily Republican frequently printed letters sent home by frontline men from Company D, painting a romanticized image of Company D in the process. Stories of the company’s heroics fueled Wooster’s enthusiasm towards its own wartime efforts, which ranged from the organization of Liberty Bond drives to the planting of victory gardens.

1 Edward Harry Hauenstein, A History of Wayne County in the World War and in the Wars of the Past, (Wooster: Wayne County History Company, 1919), 104; See also: Colonel F.C. Gerlach binder, Wayne County Public Library Genealogy and Local History Department.

Anti-German Sentiment in Wooster

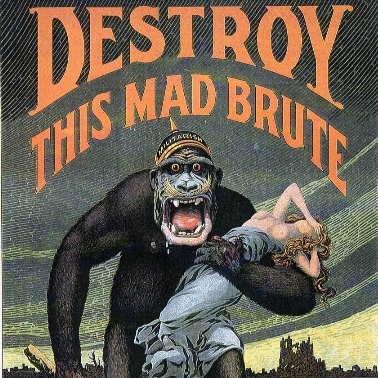

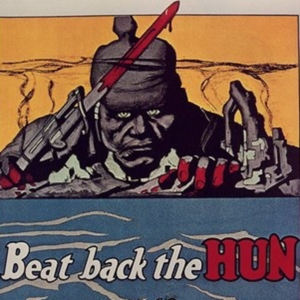

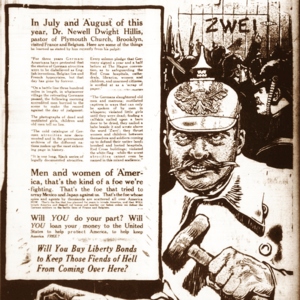

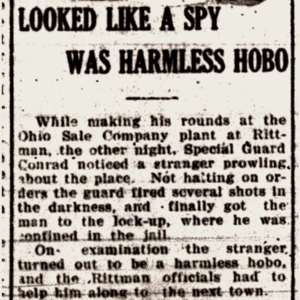

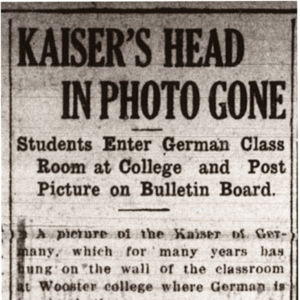

Shortly after America’s entry into World War One, President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information to bolster domestic support for the war effort. The Committee made extensive use of anti-German propaganda, which made Germans out to be great brutes that would, if unhindered, find their way to America’s shores. While this propaganda did succeed in motivating the average American to do their part for the war effort, it also created anger and paranoia towards German-Americans and German communities throughout the United States, including those located in Wooster. At The College of Wooster, students vandalized classrooms in the German Department, destroying a portrait of Kaiser Wilhelm II in the process. (1) At the same time, men working on the construction of the Federal Savings and Loan building in downtown Wooster allegedly planted a German flag atop the construction site and took pot shots at it. (2)

Despite the air of hostility that was directed towards Imperial Germany, Wooster’s German-American community was largely able to evade mistreatment for various reasons. Many of Wooster’s civic leaders were of German descent and most of the institutions that set Wooster’s German community apart from the rest, such as the town’s German newspaper, had disappeared by the time that the United States had entered the war. Despite their successful integration, World War One still marked a critical juncture for German-Americans living in Wooster, but, like most German-Americans living throughout the United States, they chose to identify themselves as Americans first and foremost.

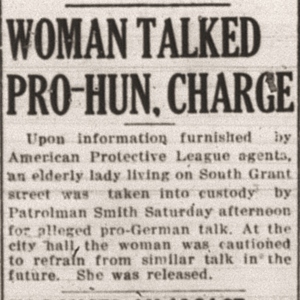

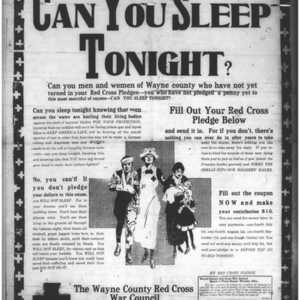

Other groups in Wooster were not as lucky and suffered discrimination based upon their association with German culture or German traditions, regardless of whether or not these associations were justified. Wooster’s Amish and Mennonite communities, which predominantly spoke German, experienced persecution for their vocal opposition to the war and their status as conscientious objectors. The Wayne County branch of the American Protective League, a nationwide organization dedicated to rooting out German sympathizers, specifically targeted Amish and Mennonite communities. (3) Local pressure towards Mennonites was so strong that in some cases Mennonites violated their pacifist beliefs and purchased Liberty Bonds. In one case Wooster residents kidnapped a Mennonite man whilst harassing him. (4) Samuel H. Miller, the editor of an Amish newspaper from nearby Holmes County, was tried and jailed for sedition after his paper printed pacifist literature. (5) Although most Mennonite churches supported the efforts of relief organizations like the Red Cross, their refusal to fully support the war effort was at odds with Wooster’s nationalistic zeitgeist.

1 “Kaiser’s Head in Photo Gone,” The Wooster Daily Republican, Apr. 7, 1917.

2 McClarran, 252.

3 Hauenstein, 186.

4 “World War I and Reconstruction Work,” Mennonite Church USA Archives, http://www.mcusa-archives.org/library/omh/pdf/3.11.pdf, 181.

5 Levi Miller. “Miller, Samuel H. (1862-1928),” Global Anabaptist Mennonite Encyclopedia Online, March 2009, http://gameo.org/index.php?title=Miller,_Samuel_H._(1862-1928)&oldid=113525.

Wooster’s Total War

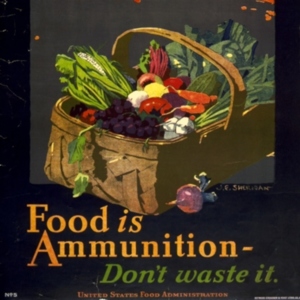

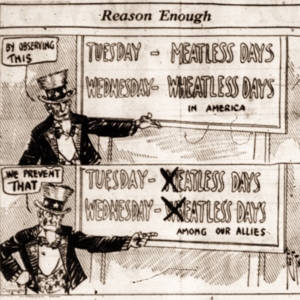

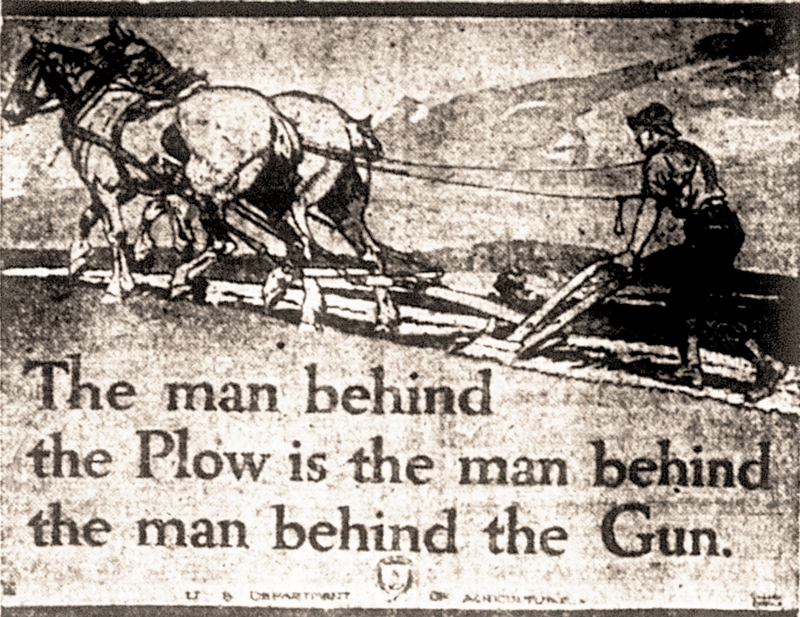

Although many young men from Wooster volunteered to fight in France, this may not have been the greatest contribution made by Wooster to the American war effort. As large sections of European farmland were replaced by elaborate trench networks, American farmers stepped in to fill food production gaps in Europe. Shortly after the United States entered World War One, Charles Thorne, the director of the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station (OAES), which helped to organize American food production for both civilian and military purposes, said:

What is the duty of the Ohio farmer in this terrible catastrophe? He is remote from the scene of the conflict; he has no military training; but he has been trained in the production of food, and in this work he can perform a service not less important and necessary than that of the soldier in the trenches. (1)

New challenges faced the OAES now that many of the men who normally labored on local farms were off fighting over seas and the demand for agricultural products had only grown. The OAES guided the expansion of local farm production throughout the war and branched out into other war-related areas as well. For instance, it taught women on the home front how to better stretch their budgets and conserve food for the good of the war effort. Mabel Corbould, a baking specialist at the OAES, pioneered several cooking techniques designed to reduce waste, which she then shared at OAES meetings and had published in local newspapers. (2) As is true in all economies that are mobilized for total war, food production became as crucial to victory as those serving on the frontline, which further enhanced the role that Wooster played in the American war effort.

1 Official Bulletin of the Board of Agriculture in Ohio Vol. VII No. I (February 1916), 69.

2 Hauenstein, 213-220.

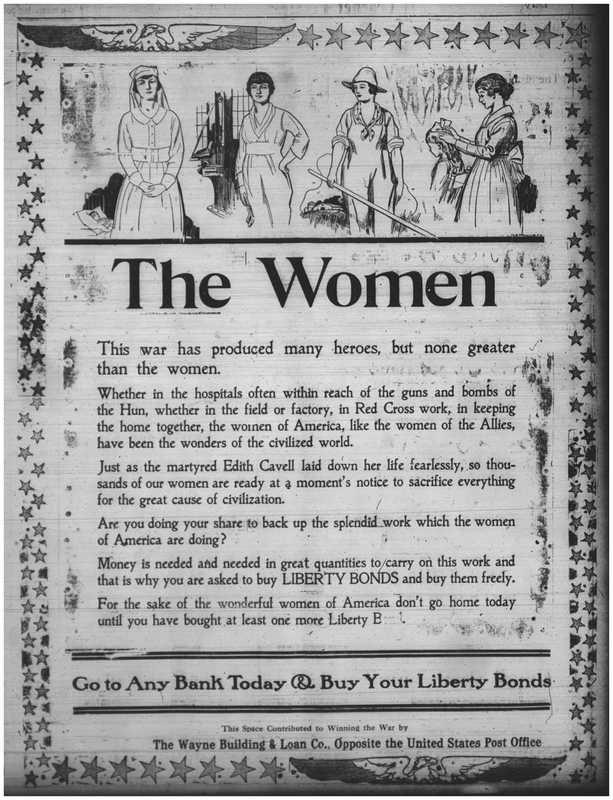

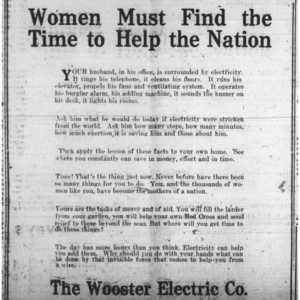

Wooster Women in World War One

Although women did not play as large a role in World War One as they would later play in World War Two, they were integral to the American war effort. Women farmed in fields and worked in factories across the United States, filling in for their male counterparts who were now fighting in France. In addition to their labor roles, women also organized a myriad of wartime charities. Mere days after the United States declared war on Germany, Mrs. R.J. Smith of the Wooster Women’s Temperance Union began a campaign to create “comfort bags” for American soldiers fighting overseas. Each of these bags would include a Bible, a book on health and illness prevention in the trenches, antiseptic cotton, soap, a washcloth, a candle, a handkerchief, a sewing kit, and a “mother’s letter.” Women also worked tirelessly for the Red Cross, creating three “Women’s Divisions” – Knitting, Sewing, and Surgical Dressing – as well as a Home Division dedicated to aiding the families of men serving overseas.(1)

Mrs. R.J. Smith of Wooster organized the local campaign to create “comfort bags” for departing soldiers.

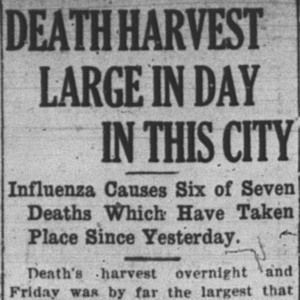

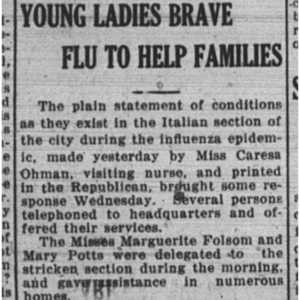

Even after the armistice was signed, the relief work that women did continued as the Spanish Influenza swept across the country in the fall of 1918. It is estimated that the Spanish Flu killed some 675,000 Americans. As the first cases began to appear in Wooster, the Home Division of the Wooster Red Cross transformed into the Influenza Committee. These brave female volunteers entered the homes of those who were stricken with the flu to provide healthcare and support for bereaved families. (2) Women played a key role in both World War One and the global pandemic that followed, which in turn expanded both the expectations that society had for women and the expectations that women had for society.

1 Hauenstein, 298-203. See also: “Comfort Bags,” Wooster Daily Republican, Oct. 18, 1917.

2 Hauenstein, 203. See also: “Ladies Brave Flu to Help Families,” Wooster Daily Republican, Oct. 30, 1918.

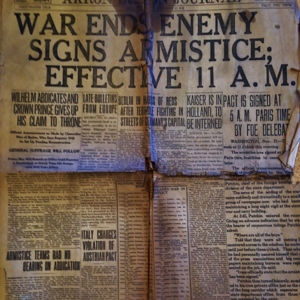

Armistice Day

On the eleventh hour of the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, World War One came to an end. News of the armistice did not reach Wooster until 2:30 a.m. when Emmett Dix, an editor at the Wooster Daily Republican, awoke to the sound of his telephone ringing. (1) By 4:00 a.m., news of the Allied victory and the end of the Great War had spread throughout the entire town. (2) The bells of the courthouse rang continuously throughout the day, schools and factories were closed, and, at 8:00 a.m., the first parade took place, yet the streets remained flooded with jubilant townsfolk until well after midnight. (1)

World War One and the pandemic that followed closely on its heels had taken their toll of the Wayne County area where seventy enlisted men had been killed overseas and nearly one hundred lives had been lost to the Spanish Flu since September of 1918. Despite these grim statistics, the people of Wooster managed to look eagerly ahead towards the return of nearly 1,500 American servicemen. These troops were welcomed home with parades, fireworks, two bands, and an extravagant banquet. The Wooster Daily Republican wrote: “With the mammoth crowd, the good music, the races, the rabbit show, the dirigible balloon, and the fireworks display, who is there that can say Wayne County’s homecoming celebration was not a brilliant success?” (2)

1 Hauenstein, 198.

2 “Great Throng Participates in Wayne County’s Welcome Home,” the Wooster Daily Republican, July 5, 1919.

How to cite this page:

MLA: “Wooster in World War One.” stories.woosterhistory.org, http://stories.woosterhistory.org/wooster-in-world-war-one/. Accessed [Today’s Date].

Chicago: “Wooster in World War One.” stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/wooster-in-world-war-one/ (accessed [Today’s Date]).

APA: (Year, Month Date). Wooster in World War One. stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/wooster-in-world-war-one/