Agricultural Politics and Farmer Values

- Home

- Agriculture and Sustainability

- Exhibits

- Agricultural Politics and Farmer Values

by Shelley Grostefon, edited by Glenna Van Dyke

Arden Ramseyer of Smithville, Ohio came from a long line of farmers, starting with his great-great-grandparents who came to Stark County in 1837 by canal to farm (the family later moved to Wayne County in 1880). 1 Arden’s father, Alvin Ramseyer, was also a farmer who started growing potatoes after he lost his dairy herd to a fire in 1932. After college, Arden followed in his father’s footsteps and enjoyed the challenging but rewarding work of potato farming. In the 1990s, the Ramseyer family, faced with hard times, added family activities and a pumpkin patch to their farm, so other families could enjoy the farm as well. With 200 years of farming experience, the Ramseyer’s have adapted to changes, including increasing government involvement in farming. The Ramseyer family exemplifies the values of Wayne County farmers; the importance of community and family, their closeness with nature and God, and distrust of big government.

Other local farmers, whose ancestors were early settlers, got their land from the local government, but other than that tried to stay out of the “predatory system of politics”. 2 Over time however, agriculture and politics became more closely intertwined. This exhibit looks at the interactions between farmers and politicians to understand the values and motivations of farmers in Wayne County. To do this, we’ll look at four periods: when Ohio became a state in 1803, when representation developed by 1846, when agricultural legislation increased with the Great Depression, and today’s era of grassroot efforts in Wayne County.

New State, New Politics

Ohio’s new settlers were deeply religious, and religion shaped their new society and government. As Arden Ramseyer put it, It was the role of the church that brought our forefathers here”. 3 While settlers came to Ohio for fertile land, they also came to escape religious persecution.4 The right to worship “almighty God” was enshrined in the state constitution, though separation of church and state was not, and belief in God was encouraged.5 The constitution even stated, “But religion, morality and knowledge being essentially necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of instructions shall forever be encouraged by legislative provision not inconsistent with the rights of conscience”.6

Though it mentioned religion, Ohio’s 1803 Constitution doesn’t speak to agriculture and Ohio’s government was less involved in farming policy.7 Farming was part of the settlers’ independent way of life, so they were hesitant to ask the government for help. However, because they received federal lands, they were dependent on the Federal Government. 8 Even in the first decades of Ohio’s statehood, farmers shaped policy to reflect their values of independence and religiosity, and these values still shape politics to this day.

Voices Finally Heard: The Election of 1846

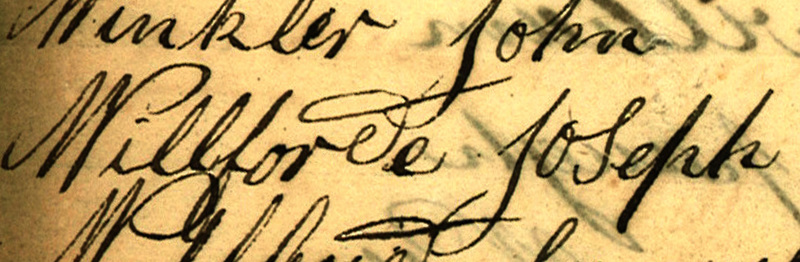

On October 13, 1846, Ohio held elections for State Senate. Wayne County’s senatorial district, which included Wayne County’s 16 townships and four in Ashland County, elected Willford, a democrat, instead of Levi Cox, a Whig, 2441-2440. 9 This was the first time that a democrat, who advocated for more poor and rural constituents, was elected to represent Wayne County. This era marked the beginning of modern participant politics nationally and in Wayne County, and farmers’ sense of community extended to include politics. 10 Even though farmers had been able to vote since 1802 (if they were white and had lived in the state for a year), Wayne County voters overall voted for Whigs, the party of elite, rather than rural, interests. 11

This election was an anomaly in Wayne County, and Willford’s election was a sign of changing times. Willford was a Greene Township farmer who lacked formal schooling, whereas Cox was a wealthy lawyer from Wooster.12 In 1850, Wayne County had eight Whig townships and eight Democratic, and while the Whig townships had more eligible voters, the Democratic townships had more farmers (54.3% to 46.8%).13 By selecting a Democratic State Senator, Wayne County farmers gained a voice in Ohio’s state government. In Wayne County and across the nation, this was the beginning of participatory politics and the relationship between farmers and politics.

Aid for Farmers: The Great Depression to Today

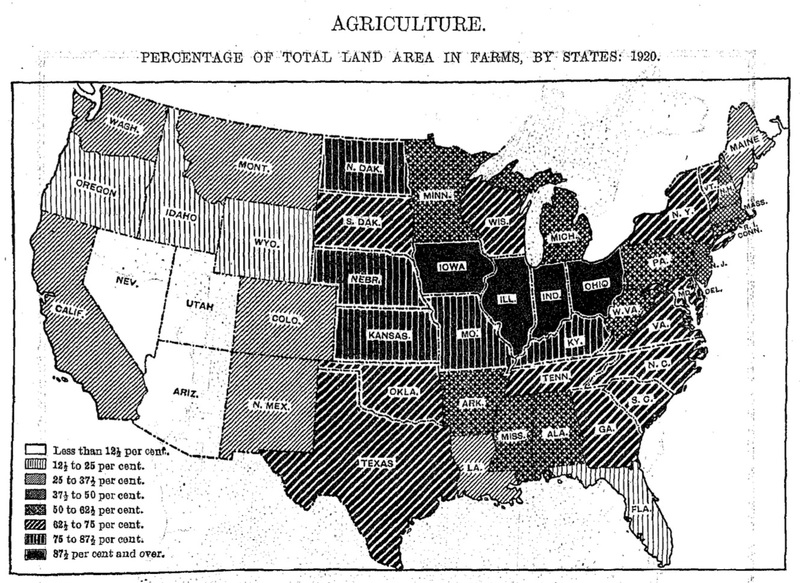

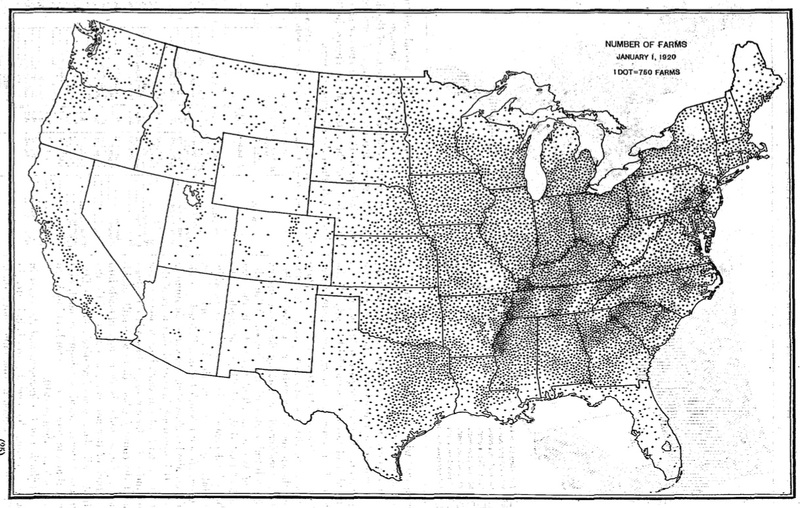

Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, agriculture remained a strong part of the economy until the Great Depression struck in 1929 and the Dust Bowl soon followed. Wayne County, which relied economically on agriculture, did not escape the destruction. To pay off debts, farmers tried to grow and sell more, but this exasperated the problem and created surpluses.14 In the decades prior, the government began to be increasingly involved, and the Great Depression “sealed the fate” of the existence of a modern Welfare State. 15 Many farmers though felt that government intervention was needed to help rehabilitate rural America.

Roosevelt rolled out his New Deal reforms in the 1930s, which helped to control the surpluses.16 Even after the Depression subsided, federal involvement in farming has continued. Today, while Ohioan farmers still maintain their independent spirit and mistrust of the government, many of them must rely on the government for land and part of their income, which comes in the form of subsidies.

Carl Redrick, a farmer in Wooster, told interviewers in 2011 that his subsidies were only a small part of his income and were decreasing. 17 He also noted, “I wish the government would get out of farming”. His wife, Carla, asked, “Sure you wanna say that on tape?”, laughing. He clarified that he doesn’t like the stipulations that come with aid, nor does he want to rely on the government to provide farmers with enough money every year. The Redricks are typical of today’s Wayne County farmers. While they don’t trust the politicians who make agricultural policy, they also rely on the government for assistance.

Grassroots Organizations and the ‘Sugarcreek Gang’

Since after the post-Civil War Depression of 1870, farmers have been involved in grassroots efforts to help themselves rather than get help from the government.18 Back then, the Populist movement and the Grange helped farmers recover from financial ruin without government aid. Today, Farmers continue to form populist movements to address the issues of the day.

In 1998, Wayne County farmers were shocked to hear that the OEPA (Ohio Environmental Protection Agency) named the Sugarcreek watershed, which covered Wayne County along with four others, one of the most impaired watersheds in the country. 19 The farmers Wayne County saw themselves as stewards of the land, who could take care of it without the government’s help, and so naturally they were shocked. 20 It turns out that their land use, including agricultural activity, stream bank modifications, and a lack of riparian diversity polluted the watershed.21

Though some were wary of the study’s accuracy, farmers teamed up with researchists from the Agroecosystems Management Program and the Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center (OARDC) to form the Sugarcreek Partners. To help fight pollution, the Partners held informal meetings to discuss current issues, water quality analyses, and education programs.22 Eventually a long-term conservation plan was developed that many in Wayne County adopted.23 Usually these types of conservation movements are not successful. However, Sugarcreek Partners, according to professors from the College of Wooster and Ohio State University who studied the group, created solidarity with farmers by focusing on their needs and values and were therefore successful. 24

Even though the Sugarcreek Partners were more successful than most, it was still difficult to convince farmers to focus on conservation. Heidi Rennecker, a farmer in Smithville, OH, mentioned in an interview that it was challenging to adapt to conservation efforts in the watershed: “[It] wasn’t cheap; we had to take it away from our personal living expenses. Most people wouldn’t do that.”25

Even in a small farming community, watershed pollution could affect millions. To combat this while still maintaining their independent spirit, farmers have worked together rather than work with the government to solve problems. While not completely independent of governmental influence, groups like the Sugarcreek Partners prove that more change is made when farmers depend on their community rather than the government.

Sources:

1 Diana R. Fisher, Activism, Inc. : How the Outsourcing of Grassroots Campaigns Is Strangling Progressive Politics in America (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2006), 112.

2 Arden Ramseyer. “In Our Own Words: Residents of Smithville and the Smithville Area Tell Their Stories Interview Summary,” interview by William Burton and Margaux Day on June 15, 2006; “About Ramseyer Farms,” Ramseyer Farms, accessed June 30, 2017, https://ramseyerfarms.com/about/.

Photograph of Arden Ramseyer circa 1934 is courtesy of ramseyerfarms.com.

3 Arden Ramseyer. “In Our Own Words: Residents of Smithville and the Smithville Area Tell Their Stories Interview Summary,” interview by William Burton and Margaux Day on June 15, 2006.

4 R. Douglas Hurt, The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1996), 211, 232, 284, 291, 299, 302.

5 Ohio State Const., art. 8, § 3, 1803.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 Fred A. Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860-1897, Vol. 5, The Economic History of the United States (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1945), 6

9 “Report of the Standing Committee on Privileges and Elections,” Ohio Senate Journal, Appendix, 1846-1847, 3. 10 Kenneth J Winkle, The Politics of Community: Migration and Politics in Antebellum Ohio (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), 4.

11 Ibid, 15, 136-137.

12 Winkle, Politics of Community, 143-144.

13 Ibid, 148; “Privileges and Elections,” 24.

14 Rachel Louise Moran, “Consuming Relief: Food Stamps and the New Welfare of the New Deal,” The Journal of American History 97, no. 4 (2011): 1004.

15 Sarah T. Phillips, This Land, This Nation: Conservation, Rural America, and the New Deal, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 2.

16 Ibid, 2-3.

17 Carl and Carla Redick, “Oral history interview with Carl Redick, Wayne County farmer, and his wife, Carla,” interview by Morgan Greer and Lindsey Bowman, December 4, 2011, College of Wooster Open Works, 8.

18 Fred A Shannon, The Farmer’s Last Frontier: Agriculture, 1860-1897, vol. 5, The Economic History of the United States (New York: Farrar & Rinehart, Inc., 1945), 294-338; William Turner, Ohio Farm Bureau Story, 1919-1979 (Ohio Farm Bureau Federation, Inc., 1982), 9-12.

19 Mark Weaver, Richard Moore, and Jason Parker, “Understanding Grassroots Stakeholders and Grassroots Stakeholder Groups: The View from the Grassroots in the Upper Sugar Creek,” (paper presented at the American Political Science Association, Washington D.C., September 2005): 14; Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, Biological and Water Quality Study of Sugar Creek, 1998 (July 15, 2000) 30; Weaver, Moore, and Parker. “A Farmer Learning Circle: The Sugar Creek Partners, Ohio,” in Pathways for Getting to Better Water Quality: The Citizen Effect, edited by Lois Wright Morton and Susan S. Brown (New York, NY: Springer New York, 2011), 203; Moore, Parker, and Weaver, “Agricultural Sustainability, Water Pollution, and Governmental Regulations: Lessons from the Sugar Creek Farmers in Ohio,” Culture & Agriculture 30 nos. 1-2 (2008): 7.

20 Moore et al., “Sustainability,” 5; Weaver et al., “Grassroots,” 16-19; Weaver et al., “Learning Circle,” 209.

21 OEPA, Sugar Creek, 11.

22 Weaver et al., “Grassroots,” 2.

23 Moore Et al., “Sustainability,” 10; Parker, Moore, and Weaver, “Developing Participatory Models of Watershed Management in the Sugar Creek Watershed (Ohio, USA),” Water Alternatives 2 no.1 (2009): 90.

24 Moore et al., “Sustainability,” 9-10; Weaver et al., “Grassroots,” 12, 15.

25 Moore et al., “Sustainability,” 9, 10; Parker et al., “Watershed Management,” 90, 96.

How to cite this page:

MLA: “Agricultural Politics and Farmer Values.” stories.woosterhistory.org, http://stories.woosterhistory.org/agricultural-politics-and-farmer-values/. Accessed [Today’s Date].

Chicago: “Agricultural Politics and Farmer Values.” stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/agricultural-politics-and-farmer-values (accessed [Today’s Date]).

APA: (Year, Month Date). Agricultural Politics and Farmer Values.. stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/agricultural-politics-and-farmer-values/.