Wooster’s Italian Community

- Home

- Cultural and Religious Communities

- Exhibits

- Wooster’s Italian Community

By Brittany Previte, revised by Glenna Van Dyke

In the late nineteenth century, industrial America was booming and seemed to many immigrants to be the land of promise and plenty. Italians joined the millions flocking to America’s shores, and some found their home in Wooster, Ohio.

Italians had been coming to Wooster as early as the 1860s, when Raphael and Angelina Massoni settled in the area now known as Lucca Street. 1 Raphael was even the first Italian in Wayne County to become an American citizen on October 13, 1868. 2 In the years following, Italians formed their own nurturing community that was known as Wooster’s “Little Italy”. With the support of their neighbors, Italians flourished in Wooster. They sent for their loved ones, helped newcomers settle in, and even established an official aid society to help their neighbors. Today, Wooster’s Italian roots are an important part of the community’s heritage.

The Journey to Wooster

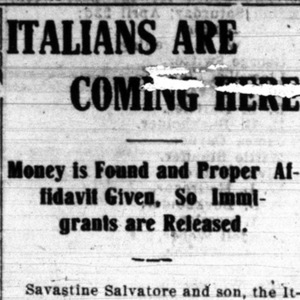

Despite the pouring rain on April 26, 1910, Vincent J. Cincinatti could not stop smiling according to Wooster Daily News.1 He had just received word the day before that his fiancée, Carmello Tomosseti, had arrived in New York City and headed for Wooster. After enduring six painful years and a railroad accident where Cicconetti lost his foot, the couple would be reunited.

From 1880 to 1920, a wave of “New Immigration” was sweeping across America, and immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were arriving in droves. Though most of these immigrants went to large cities, some settled in small towns like Wooster, to work in mines or on the railroad. 2 Some were sent by labor recruiters while others came through networks of other villagers, such as Sabbatino Di Lucca, who came with others from the Collepietro village. 3 Many others still came over through friends and family. Young men like Cicconetti sent for their sweethearts and others like Andrew Massaro encouraged their families to come over.

The Generous DiGiacomo Family

Italian immigrants in the early 20th century faced many challenges, and, instead of turning to the government to help, they often relied on their friends and neighbors in times of need. They created their own social and professional networks and well-established Italians often helped newcomers.

One such generous community member was Joseph DiGiacomo, named “The best-hearted man in Wooster” by the Wooster Daily. 4 He came to America in 1900 with his Uncle and in 1920 established the “DiGiacomo Building” next to the railroad station. 5 The three-story building had over 40 rooms and towered over the tracks.6 DiGiacomo opened his grocery on the first floor and provided housing for many new Italian immigrants on the upper floors.7 He quickly became a mentor for newcomers and helped them navigate the complicated new world and gain citizenship.

DiGiacomo’s daughter, Rose, opened a restaurant in the DiGiacomo building. She opened her doors at 5 a.m. and invited the rail workers for breakfast. Taking after the generosity of her father, she provided food and rent for the hungry and poor in Wooster and volunteered at St. Mary’s Church. In 1963, she received a Papal award for her charitable efforts, and in 2008 DiGiacomo Green was dedicated where the DiGiacomo building once stood, honoring the DiGiacomo family and the Italian immigrants they helped.

Official Aid Societies

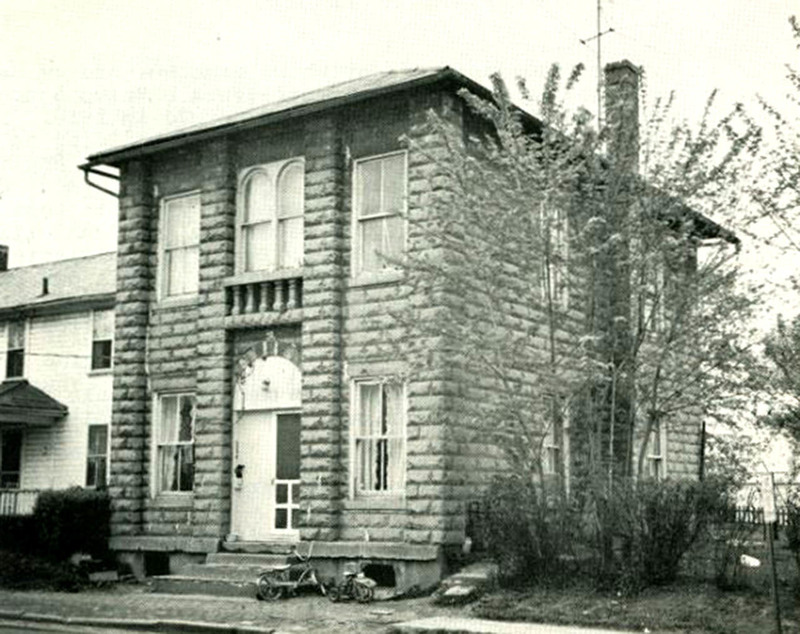

Besides their neighborly generosity, Italian communities often set up more formal organizations to aid immigrants. 8 Joseph DiGiacomo, Andrew Massaro, and Benjamin Zarlengo created the La Societa’ di Beneficenza e Muto Soccorse (Society for Beneficence and Mutual Aid) in 1910. 9 There, they taught English classes, prepared immigrants for citizenship exams, provided financial aid, and introduced Italian culture to locals. Classes and meetings were held in a building called the “Town Hall”, a two-story brick building on Palmer Street.

Today, the Italians’ charitable ways live on in the Lamplighter’s Club. The Lamplighters, like the original societies, seek to preserve Italian heritage and help others in the community. They continue to be a beacon for goodwill in Wooster. 10

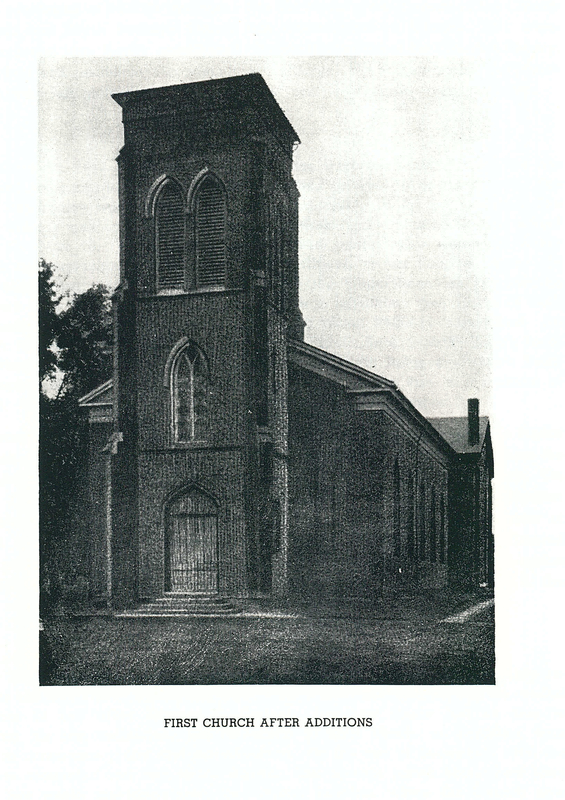

Wooster’s Italians and the Catholic Community

Italians coming to Wooster found an already thriving Catholic community that had existed since 1812, with the first Catholic priest, Father Edward Fenwick O.P, coming to Wooster as early as 1817. 11 The first Catholic church built was St. Mary’s of the Immaculate Conception, in 1847. Italians quickly joined this catholic community, sent their children to Catholic schools and joining Catholic congregations. Briefly in 1907, the Italian Community considered forming their own congregation and the received permission from the Bishop of Cleveland to do so. However, this was dropped two years later when Church officials determined that the church would not have enough parishioners. 12

As they settled into existing Catholic spaces, they brought their Italian traditions with them. The Feasts of Saint John and Anthony were celebrated in the Abruzzi region, the homeland of many Italian families in Wooster. On this day, there is a village procession to the church, mass, games, dancing and celebration. The Italian Society organized the first Feast in Wooster in 1917. The festival was on June 24, and local Italians paraded a statue of Saint John from Town Hall to St. Mary’s. The statue was carried on men’s shoulders while women and children followed them singing “Evviva Maria” (Mary is Alive!). Today, Saint Mary’s is the statue’s permanent home. 13

“The Hill”: Wooster’s Little Italy

When Italians arrived in Wooster, the “Hill” already had many Irish, German, and French residents. Originally Italians lived near the Massoni allotment, and later the Massaro allotment when Andrew Massaro started selling lots in 1912.14 Little Italy was all about community, and after a long day on the Pennsylvania Railroad or the Wooster Brickworks, neighbors would sit on their porches and talk in the evenings. Lucille Santangelo, a former resident of the Hill, explained, “We were very good at neighboring.” On the Hill, everybody knew everybody, and neighbors visited each other and shared what they had whenever they could. “Everybody had a garden–the bigger, the better,” Santangelo said. When the gardens were ripe, neighbors would bring over plenty of fruits and vegetables to share. 15

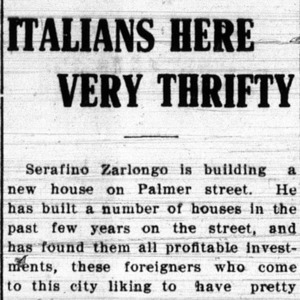

While hostility towards immigrants was more common in the big cities, Wooster had some element of that as well. Articles in the Wooster Daily News comment on the “foreign element” in Wooster.16 John Yankello observed in a 1979 Daily Record article that “There has always been a dividing line between our end of town and the north end.”17 While some were suspicious of local Italians, the Italians in Wooster continued to serve their communities and country. After America entered WWI, Wooster’s Italians joined the ranks of volunteers for Company D, 146th Infantry, 37th Ohio Division. Carlo Coppola was the first man in Wayne County drafted for military service, seeing action at St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne.18 Second generation Italians volunteered with the same spirit in WWII. Men and women of the East End served their country as soldiers, nurses, officers, counter-intelligence agents, and crew members in the navy.19

Although now most Italians are dispersed throughout town, they keep their cultural heritage and their sense of community close to heart.

Take a tour through Wooster’s own “Little Italy.”

Sources:

1 “Crosses Sea to Join Her Lover Who Waited Long.” Wooster Daily News. April 26, 1910.

2 Diane Vecchio, “”Ties of Affection: Family Narratives in the History of Italian Migration”” Immigration, Incorporation & Transnationalism. Ed. Elliott Robert. Barkan. (New Brunswick: Transaction, 2007.) Print.

3 Dominic Iannarelli, A Touch of Italy in Wooster. (Wooster: The Daily Record, 1968).

4 David T. Beito, From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State: Fraternal Societies and Social Services, 1890-1967. (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000).

5 “Italians Are Coming Here,” Wooster Daily News. April 25, 1910.

6 Dominic Iannarelli, “Joseph DiGiacomo’s Work Done,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster. (Wooster: The Daily Record, 1968).

Elinor Taylor. “56-Year-Old ‘High-Rise’ Built by Joe DiGiacomo,” Daily Record. August 4, 1978.

7 Ibid.

8 David T. Beito, From Mutual Aid to the Welfare State: Fraternal Societies and Social Services, 1890-1967. (Chapel Hill and London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2000) 19.

9 Dominic Iannarelli, “The Italian Society of 1910,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster. (Wooster: The Daily Record, 1968).

10 Ibid., Iannarelli, “The Lamplighters Social Club,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster.

11 “High Church Dignitaries, Former Pastors and Assistants Will Come to Wooster for St. Mary’s 100 Anniversary,” The Daily Record. 3 Oct, 1947

12 Dominic Iannarelli, “Scenes and Events: Through a Keyhole,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster. (Wooster: The Daily Record, 1968).

13 Ibid., “Saints John and Anthony.”

14 Dominic Iannarelli, “Little Italy,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster. (Wooster: The Daily Record, 1968).

15 Lucille Santangelo, interview by Brittany Previte, Wooster, OH, June 23, 2014.

16 “Italians Here Very Thrifty,” Wooster Daily News. August 27, 1910.

17 Paul Locher, “People on ‘The Hill’ Proud of Heritage,” The Daily Record. March 3, 1979.

18 Iannarelli, “WWI,” A Touch of Italy in Wooster.

19 Ibid.

How to cite this page:

MLA: “Wooster’s Italian Community.” stories.woosterhistory.org, http://stories.woosterhistory.org/woosters-italian-community/. Accessed [Today’s Date].

Chicago: “Wooster’s Italian Community.” stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/woosters-italian-community/ (accessed [Today’s Date]).

APA: (Year, Month Date). Wooster’s Italian Community. stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/woosters-italian-community/