Delaware Encounters

- Home

- Early Settlement

- Exhibits

- Delaware Encounters

By Scott McLellan, revised by Jordan Wilson, Glenna Van Dyke, and Spencer Gaitsch

When learning about early American history, it is important to ask questions. What was here before European settlers? What lost storied does this land have to tell, and who were the people who called it home? This exhibit explored the brief “pre-history” of the area now occupied by Wooster, offering a glimpse into encounters with the Lenape or Delaware people of Ohio.

Pre Lenape Indigenous Populations

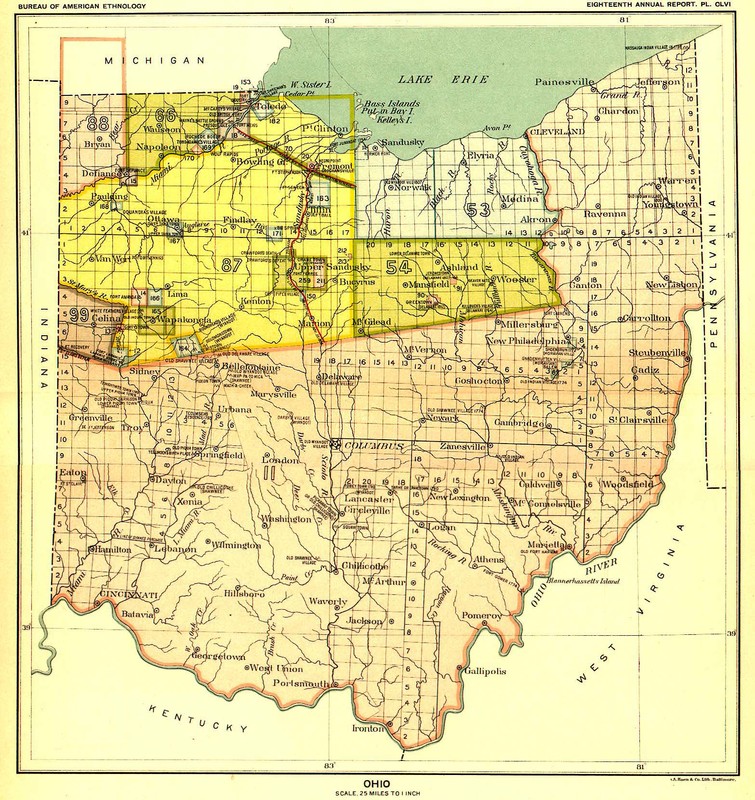

The area now occupied by Wooster originally served as the hunting ground for the Eriehronon, more simply known as the Erie. It is estimated that, by 1656, the Iroquois League had come to the area and scattered the Erie tribes from the area.1 While fleeing west from European settlement, they encountered nations of the League, pushing them even farther west into the land once occupied by the Eriehronon.2 When settlers arrived they encountered a hunting land shared by the Deleware, Shawnee, and Wyandot.3

For more on the indigenous populations of Ohio, see the Ohio Historical Society’s online exhibit, Virtual First Ohioans.

(Right) This memorial was built by the City of Wooster to recognize the crossing of three major indigenous trails that intersected in what is not Wooster. While it stands a few hundred feet from where they intersected upon the Larwills’ arrival, it pays homage to the huge role pre-settler, indigenous infrastructure played in Wooster’s success.

Treaty of Fort Industry

The Treaty of Fort Industry was just one small part of America’s boundless quest for expansion in the 1800s. Signed on Independence Day, 1805, it was the agreement that gave the United States the rights to the land that Wooster stands on today. Before the Treaty of Fort Industry was signed, the Treaty of Greenville secured the land that is now southern Ohio.4 The agreement brought about by the Treaty of Greenville was tense at best, as Native Americans grew suspicious of U.S’s growing demands for land. Soon enough, President Thomas Jefferson ramped up his aggressive land expansion policy, eventually pressuring tribes in the area to sign away their rights to the land that would become Wooster and the area northwest of it. This land transfer soon came to be known as the “New Purchase.”5

Beaver Hat Town

In 1808, surveyors of the New Purchase arrived near what is now the Wooster Cemetery where they came upon a small encampment of Delaware Indians settled within an apple orchard.6 The encampment’s leader, Chief Pappellelond, referred to the area as “Apple Chauquecake,” or “Apple Orchard,” and some believe that the orchard was one of the many planted by Johnny Appleseed.7 The area covered by Pappellelond’s Chauquecake, located at the intersections of the Cuyahoga War Trail, the Great Trail, and the Killbuck path (now Routes 585, 3, and 83 respectively), served as an important commercial center throughout the westward expansion of the United States.8 The area grew into a town and later came to be known by the English name that was given to Pappellelond: Beaver Hat Town.

(Right) Oak Hill (Wooster) Cemetery

Massacre at Beaver Hat Town

Beaver Hat Town, now covered by the area from Schellin Park to the Wooster Cemetery, is said to be the sight of one of the grisliest events in Wooster’s history. As local historians tell it, a band of sixteen Sandusky Indians approached the Raccoon Creek settlement, near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and befriended its residents.9 Overnight, for an unknown reason, they attacked the town from within, burning several houses and killing five settlers.10 In response, Captain George Wilkes led a group of thirty white men to pursue them. The legend goes that Wilkes, having been kidnapped by Native Americans at a young age, knew the language of the area. Using this to call a lone native who was fishing back to the encampment, the group succeeded in getting its revenge against the alleged Sandusky perpetrators. Upon reaching the indigenous settlement in the apple chauquecake (apple orchard), the men massacred the natives in the area.

(Right) A view from the intersections memorial, this is potentially a part of the area that was once occupied by Chief Pallelelond’s apple orchard. It is now covered by routes 30, 83, and 3.

Citations

1 Lindsey Wilger Williams, Old Paths in the New Purchase, (Wooster, OH: Atkinson’s Printing, Inc., 1983).

2 “Deleware Indians,” Ohio Historical Soeicty, accessed 6/13/2013, http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Delaware_Indians.

3 Paul Locher, When Wooster Was a Whippersnapper: Two Hundred (or so) yarns about Wooster for Two Hundred Years, (Wooster, OH: The Daily Record, 2008).

4 Douglas R. Hurt, The Ohio Frontier: Crucible of the Old Northwest, 1720-1830 (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1996).

5 Lindsey Wilger Williams, Old Paths in the New Purchase (Wooster, OH: Atkinson’s Printing Inc., 1983).

6 Ben Douglass, History of Wayne County, Vol. 1 (Indianapolis, IN: B.F. Bowen & Company, 1910).

7 Paul Locher, “Johnny Appleseed popularity part of the lore,” The Daily Record, January 9, 2008, http://devserver.the-daily-record.com/news/article/3111792.

8 Lindsey Wilger Williams, Old Paths in the New Purchase, (Wooster, OH: Atkinson’s Printing Inc., 1983).

9 Ibid.

10 Ben Douglass, History of Wayne County, Ohio (Indianapolis, IN: B. F. Bowen & Company, 1910).

How to cite this page:

MLA: “Delaware Encounters.” stories.woosterhistory.org, http://stories.woosterhistory.org/delaware-encounters/. Accessed [Today’s Date].

Chicago: “Delaware Encounters.” stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/delaware-encounters/ (accessed [Today’s Date]).

APA: (Year, Month Date). Delaware Encounters. stories.woosterhistory.org. http://stories.woosterhistory.org/delaware-encounters/